An Interview with Mick by Marty Gunther

Published in Blues Blast Magazine 12/24/23

Angels come in all forms, and in the world of blues, you don’t have to look any farther than Mick Kolassa to see one in the flesh.

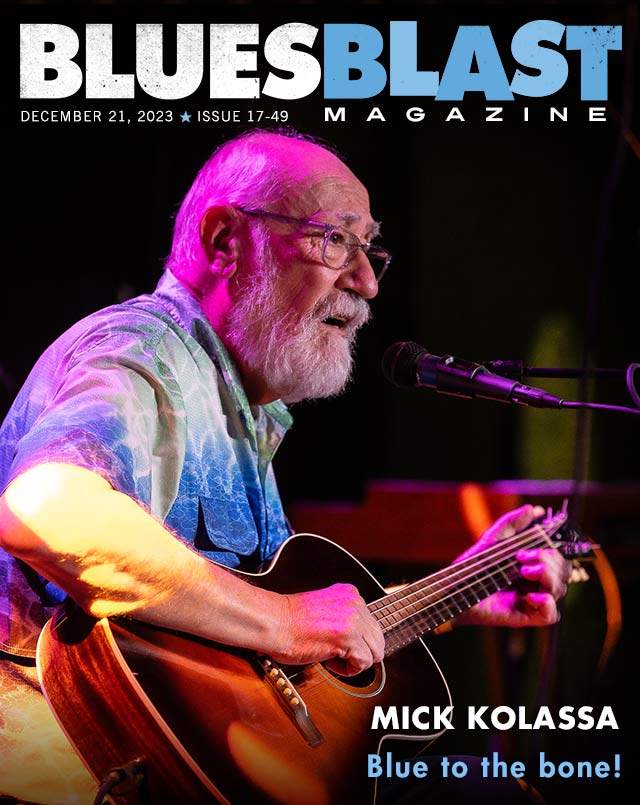

Known as “Michissippi Mick” to his fans because of his Michigan roots and his three-decade presence in Mississippi or as Uncle Mick to his many friends, Kolassa’s a former member of the board of the Blues Foundation who definitely looks the part of a bluesman.

He’s an easily approachable, heavily bearded and warm man, but Kolassa’s far more than that. A former college professor with a PhD in marketing, he also spent years in the pharmaceutical industry and has been a mover and shaker in several other non-profit organizations, too.

One of the busiest recording artists on the planet since his “retirement” a decade ago, Mick performs in what he calls “free-range blues” – a hybrid style that incorporates everything from acoustic to electric, from Delta to Chicago, from country to rock and reggae, too. And he exhibits generosity beyond compare.

“I was born in the town of Three Rivers just south of Kalamazoo,” says Mick, who’s been based out of Memphis for a few years but is planning to relocate back home sometime in the year ahead. “But I grew up in (the neighboring small town) Sturgis, which was recently named the most redneck town in Michigan, and it’s earned it. You see more Confederate flags there than I’ve ever seen in Mississippi.

“Dad listened to big bands, and my mom listened to classical and older sister to popular music. So I grew up around all that. People ask me: ‘What’s your favorite song?’ I don’t have one because it’s so situational.

“But I do have some favorite pieces of music…Beethoven’s ‘Ninth Symphony’ and Gershwin’s ‘Rapsody in Blue’ — played by an American orchestra because I’ve never heard a European orchestra that can get it right. The third is Benny Goodman’s ‘Sing, Sing, Sing’ done live with Gene Krupa playing drums. Those three pieces are filled with so-o-o much emotion.”

Mick fell in love with the blues at age 14 – “and I got here through Hank Williams,” he says. “Hank learned to sing and play guitar from an old black bluesman (Rufus ‘Tee-Tot’ Payne) in Georgiana, Ala., which is what a lot of country people did at the time.

“I’d seen Your Cheatin’ Heart — the biopic starring George Hamilton as Williams — on TV, probably Saturday Night at the Movies when they had that. I said to myself: ‘I really like some of those songs…they’re cool!’ So I went to the appliance store stereo department to buy Hank Williams’ Greatest Hits. And sitting right next to it in the rack was Robert Johnson’s King of the Delta Blues Singers.

“I had a couple of extra bucks, and said to myself: ‘This is interesting…’ and I bought it.

“I wore that damned record out, but still have my second copy. I literally wore the track off the ‘Travelin’ Riverside Blues.’ That song just grabbed me and wouldn’t let go, and I just needed to dig deeper. I was listening to Robert Johnson before I ever heard of Eric Clapton, and I bought John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers because there was a Robert Johnson song on it and for no other reason.

“But I was also very fortunate because — being there in the Upper Midwest on a humid summer night, I could pick up WLAC in Nashville and listen to John R. spinning all the best blues and rhythm-‘n’-blues…the real deal…Muddy Waters, Etta James, Howlin’ Wolf, a little bit of Sam Cooke and saying to myself: ‘You know, I really like this music.’

“Like everybody else at the time, I got into folk and rock, too,” Kolassa admits. “I started out playing the drums, but I picked up guitar because it was easier to carry around. And it was much easier to pick up chicks as a guitar player. And I was singing, so it just made sense to do it.

“But the first songs I ever did in public were blues. I was playing drums with some guys who played some blues, and that’s just always been the way I went.”

Little did he realize it at the time, but in 1969, Mick was one of the most fortunate blues lovers the world ever. At age 17, he got to attend the first-ever Ann Arbor Blues Festival, which featured a lineup beyond compare, a three-day event that was as significant as Woodstock, which was held two weeks later.

Muddy, Wolf, B.B., Freddie and Albert King were all present. And Junior Wells, Jimmy Dawkins, Luther Allison, Otis Rush, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, J.B. Hutto, Roosevelt Sykes, Big Joe Williams, Clifton Chenier, Sippie Wallace, Sleepy John Estes, Yank Rachell, Big Mama Thornton, James Cotton, Big Mojo Elem, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Son House, T-Bone Walker and Magic Sam also performed, too.

“And it was the very first blues festival for Bonnie Raitt and Shaun Murphy,” Mick notes.

“By the time I heard Led Zeppelin sometime later, I was so into Muddy that I thought they were raping his music, and I didn’t like what they were doing. A lot of guys my age got into the blues because of Cream, Zeppelin and the Allmans, and they define blues that way, and that’s fine. But I can’t.

“And I didn’t like the Allman Brothers’ whitewashed version of ‘Hoochie Coochie Man’ either ‘cause I’d already heard the real deal.”

The cultural appropriation of the music has always been both contentious and controversial, Kolassa says, and it’s come in different forms within the black community, too.

“I’ll never forget this…I was stationed in Germany in 1972,” he says, “and I was in my barracks. I was listening to Muddy. I had it cranked up loud because I just loved it, and there was this violent beating on my door. I open it and there were about 11 black guys from the unit downstairs, demanding: ‘Turn that fucking slave music off right now!’

“And I understand it because they associated it with the bad times. It’s interesting…you get down to Mississippi and it’s always been the music of home. But in the North, it was something entirely different.

“But I stuck with it. And I saw Muddy three more times when I was in Germany – and Wolf, Johnny Winter and so many other folks.”

Kolassa performed regularly when he was in uniform. He wed another G.I., Molli, who was thrilled that he was a musician. But when he tried making a living back home by playing solo and acoustic, he quickly realized there was no future in it for him — or his new family – by gigging at the local Holiday Inns and playing a circuit that also included a young rising star, John Hiatt, who’d just signed with a major label.

“But John did okay,” Mick jokes.

The decision led to Kolassa enrolling at Eastern Washington University in Pullman, his wife’s hometown, where he earned both a bachelor’s and an MBA degree. He subsequently relocated back to the Wolverine State in 1980, agreeing to teach a few classes at a local college, and something he continued to do after the Upjohn Company – now a part of Pfizer but then the first mass marketer of cortisone and inventor of Xanax, Halcion, Motrin and Rogaine – offered him a position that led to a long, successful career in the pharmaceutical industry. He took the job on the same day the world lost John Lennon.

“I also started hanging out with a bunch of avid fishermen,” he says, “and joined up with Trout Unlimited. They were all musicians, and we started playing together – everything from jazz to bluegrass – on fishing outings – at the same time I was listening to blues. That brought me back into playing.

“We eventually cut an album of original fishing songs called Trout Tunes and Other Fishing Madness, which still gets some radio airplay today. After Earth Day, I’ll still get a notice that someone played my songs, ‘Save the Water’ – the first reggae song I ever wrote — or ‘You Can Have It If You Want It.’”

Kolassa eventually left Upjohn to teach fulltime at Nazareth College, a small school in Kalamazoo, where he was “the professor of M.” If it started with ‘m,’ he taught it – marketing, management, micro-economics, money, banking and credit, and, of course, a course in the blues. A former all-girls school that was only master’s degree-granting Michigan institution without an athletic program, it eventually bankrupted itself into non-existence after the new president started one.

“I could see that coming,” Mick remembers, “and I just started consulting and teaching part-time at a couple of places. I also started working on a doctorate, and got recruited by Sandoz Pharmaceutics – the Swiss-German conglomerate that invented LSD and Screaming Yellow Zonkers, making the ‘60s possible. They wanted me to start an economy policy department for them at their offices in New Jersey.”

Never someone who thought of himself as a “corporate guy,” Kolassa was doing “okay,” he says, but he left Sandoz to work as a consultant and lecturer – partially, he says, because, as a Midwesterner, he found it impossible to adjust to an East Coast lifestyle.

Soon after, he landed in Oxford, Miss., when Mickey Smith, a senior member of the University of Mississippi’s School of Pharmacy and a specialist in pharmaceutical marketing, invited him down to speak and then offered him a teaching post along with the simultaneous opportunity to pursue his PhD at his campus.

“I immediately went home and said to my wife – who made me promise to never live in a state without mountains – ‘honey, this is what I want to do… I want to take an $80,000 cut in pay and move to Mississippi and right on the edge of the Delta,’” he recalls. “And she said: ‘If that’s what you want to do, that’s what we’ll do.’

“We go down there, and all of a sudden, we’re surrounded by the blues. We get invited to a party and the band’s Bill Perry’s Howlin’ Madd and the Relaxations. Bill and I eventually became really good friends, but I was in awe – and it was so-o-o much fun.

“And Dick Waterman (who was one of three young men who ‘rediscovered’ Son House before booking the Newport festivals in the ‘60s and eventually managing Bonnie Raitt, Junior Wells and several of the first-generation blues stars) moved to Oxford the same year I did, and we eventually became friends. The magic of sitting in Dick’s dining room and looking through a couple of hundred thousand photos that he’s taken is just amazing.

“It’s just stunning what he witnessed, but also been a big part of.”

As he immersed himself in the local blues scene, Mick started playing out on occasion while working diligently behind the scenes in his chosen field. He eventually devised the formula that pharmaceutical companies use to determine the pricing of new products – a value-based strategy in which they charge more for drugs that keep folks working, functioning properly and out of the hospital – a lofty, virtuous idea that, he admits, the industry eventually began to abuse.

He found himself so busy consulting and more that he founded a consulting firm, Medical Marketing Economics, with former students and left his fulltime position at Old Miss to teach a few courses. And in his spare time, he also wrote the book The Strategic Pricing of Pharmaceuticals.

He turned his back on the pharmaceutical industry entirely more than a decade ago when he became disgusted by the corporate greed that many of the firms exhibited when using his business model.

Mick has devoted himself almost exclusively to the blues since a chance meeting with guitarist Jeff Jensen at the Bluesberry Café in Clarksdale during the Juke Joint Festival in the early 2010s. “Jeff was playing with Brandon Santini at the time,” he remembers. “And my brother-in-law, Ted Todd, and I were putting a show together in Spokane, where he lived, and thought they’d be a great addition to the show.”

A Keeping the Blues Alive honoree, Ted passed away in Mick’s house in 2015, but not before becoming a blues legend in the Pacific Northwest for his work in radio, as an event producer and more. A regular visitor to Memphis for the International Blues Challenge, he was responsible for getting Kolassa to serve as a judge at the festivities and later as a Blues Foundation board member, too.

Once on the board, Kolassa used his economics know-how to conduct impact studies to show that the foundation deserved more local funding because of all the money the IBCs and Blues Music Awards were bringing to the city. It was something he’d done in the Bahamas and Belize before for the Bonefish and Tarpon Trust, another non-profit that promotes stewardship of fisheries.

He was also instrumental along with Teeny Tucker in the restoration of the Riverside Hotel in Clarksdale, Miss. A place that’s housed blues legends since the ‘40s, it previously served as a hospital and is the location where Bessie Smith, the empress of the blues, took her last breath in the ‘30s. Without the tireless efforts of Mick and Teeny, who started a GoFundMe campaign and penned a song about the building, the National Parks Service would have never provided the major grant that it did to finish the project.

Mick sat in with Jeff and Brandon for a couple of tunes that day after also being invited up by an earlier act. From that point onward, Jensen regularly welcomed Kolassa to the stage every time he was in the audience.

“Eventually, I started doing some of my original songs – tunes that told a story, not simply a disjointed rhymes and cliches,” he says, “and Jeff said: ‘Mick, you need to cut an album of this stuff.’ He was the one who got me back into performing.

“And before I knew it, there I was. When I started the company, I told my grad-student partners: ‘Your job is to see that I retire comfortably.’ And I think they’ve done a pretty good job. It eventually got to the point where I said: ‘I don’t want to do that anymore. This is what I want to do.’”

His concept for free-range blues came about, he says, because he grew weary of being asked what flavor of the music he played.

“Most artists have a style,” he notes, “Doug Deming, who plays jump, has a style that’s very distinct, and Victor Wainwright’s style is distinctive, too. They’ve got a sound that really works for them. Other people identify themselves as Chicago, Memphis or Delta bluesmen. Well, I play all of it. I finally said; ‘I’m gonna call it ‘free-range blues’ ‘cause that’s what I do.

“I actually copyrighted it, but it’s really something that isn’t new. If you sit down and listen to Mississippi John Hurt and Son House – two contemporaries that were a planet apart in terms of their stylings — they were doing it. So were Skip James and Josh White. They all did something different, and it’s all blues.

“I’m a child of rock-‘n’-roll and I like a lot of electric blues – as long as you let it be blues. I’ve got a song on my latest album entitled ‘Sugar in My Grits.’ That comes from a conversation I had with my friend Redd Velvet, who said: ‘All these white boys come down here to the South and learn about real blues and what it’s all about, and the first thing they do in the mornin’ is get up and put sugar on their grits.’

“It’s a wonderful metaphor of trying to put metal into blues. I wrote that song, and the bridge is ‘Muddy never played a 20-minute solo, and Wolf didn’t own a pedal board. Willie Dixon told stories with every one of his songs, but do lyrics even matter anymore?’

“Frankly, I listen to a lot of the new stuff, and I think people are just finding words that rhyme to fill in between the guitar solos. It’s fine if that’s what you enjoy. But all of a sudden, you’re playing rock, you’re not playing blues. I generally associate with musicians who feel the same way. That’s why Bob Corritore didn’t have to think twice about playing on that song.

“Don’t get me wrong, though. I love rock, but it just isn’t blues. And I’ll throw some rock into my shows if that’s what the people want. I can and do love country, too. I love it all.”

Kolassa debuted free-range blues on record in 2014 with the well-received CD Michissippi Mick. All of his 13 subsequent releases have achieved success in both airplay and on the charts, and all but one have been produced by Jensen with a core group of Memphis-based musicians, Grammy winners and other heavyweights included.

And he’s donated all of the gross proceeds of the Blues Foundation and two of its charities, the HART Fund, which benefits artists in need, and Generation Blues, an outreach program that supports young artists and brings new players and fans to the music.

“I think I did two or three albums when I was still with my company,” Kolassa notes. “I was recording, putting bands together, performing and touring. In 2016, I started my own label, Endless Blues Records, which was a spin-off from a company that my brother-in-law and I had started.

“I said: ‘You know what…I’ve made all these albums and made all these mistakes. Now I understand how to do things. Time to help some friends out.’ So I reached out to Eric Hughes, Tullie Brae and In Layman Terms to record. I was working with the Pinetop Perkins Foundation and met these kids and they blew me away. I’m Uncle Mick to them, and they’re now dear friends. From the beginning, the idea of the label was just to help independent artists.”

That roster also includes Tennessee Redemption, Dexter Allen, Chris Gill and the late Kern Pratt, too.

“Unfortunately for me, though, I started the label just in time for COVID and streaming. So things aren’t as easy as they used to be. I do okay with streaming, and I’m working right now to put together a video to help artists know what they need to do.

“Here’s a little thing that most artists – people who write and perform their own songs and not playing just in their local bar — are totally unaware of…both ASCAP and BMI have programs that – if you’re performing your own music – you can get paid for it.

“I don’t know about ASCAP, but BMI will give you about $2.50 every time you sing one of your own songs at one of your gigs. If you’re doing four or five gigs a week and 20 of your own songs each night, that’s $250 a week you could be getting if you just bothered to submit your own playlist.

“It’s called BMI Live, and it’s real easy to do. ASCAP’s, I believe, is called ASCAP on Stage. And make sure you belong to Songtrust and Sound Exchange, too.”

Just recently, Mick says, one his songs, “Running to You” off the For the Feral Heart album, was picked up by SiriusXM and got played two or three times a day for ten weeks straight, earning him between $28 and $30 for each spin, depending on the size of the audience – something that wouldn’t have occurred without his association with Sound Exchange. It’s money that BMI would never have collected because BMI doesn’t monitor those types of plays. A relationship with Songtrust provides coverage for the same type of spins overseas.

“You have to be associated with all four organizations to insure you’re getting the right amount of money,” he insists. “I’m working with folks who are working now to help musicians understand this…you’re making money, but the money can’t find you. I was just lucky enough to pay attention – whereas a lot of folks don’t.

“Even some of the best business-oriented people in blues miss some of these things because they’re not aware of them because the whole music industry was designed for the major labels to make money and take advantage of the artist. All of the labels know this stuff, but most independent artists – and the people that manage them — don’t.

“And I’ve got to thank Michael Freeman, the Grammy-winning producer, who had me fill out an application with Sound Exchange because, all of a sudden, I started making a lot more money because I’d had songs that played on Sirius before but had no way to collect it.

“I want to help folks out, and that’s an important message to impart.”

When we spoke, Mick was already planning out his 15th and 16th albums. “I think I’m going to call 15 Free-Range Blues because they’re going to be four distinct parts to in,” Mick says. “One’s going to be acoustic, another classic blues and Southern soul-blues and some jazz-oriented blues with four different bands in four different sessions.

“And I also want to do another album of duets. I did the album Double Standards a few years ago. It still gets a lot of play, and it was so-o-o much fun doing it with my friends. I think I’ll call it ‘Another Round of Doubles,’ and I’ve already got some folks lined up for it.”

For the better part of 50 years, Kolassa says, he’s been immersed in the blues, and there’s one thing he stresses that everyone should never forget: the true origin of the music.

“It certainly comes from the African-American experience,” he exclaims. “There’s no way around that. You know there’s the button that says ‘No black, no white, no blues’ — I cross out some of it so it says no black, no blues. It’s 95 percent African-American. It’s important for everybody to understand that. And it also has five percent international roots.

“You know the Scotch-Irish who came here and helped create bluegrass? Well their indentured-servant cousins were picking cotton alongside the black slaves and introduced Celtic music – which is based around the 1-4-5 structure that we have in the blues — to them. There’s nothing like that now in Africa.

“We have guitars in the blues because of the migrant workers from Mexico who came to the Delta. Previously, the blues was played on banjos and fiddles. Robert Johnson played tunes in open-G, Spanish tuning because that’s what mariachi’s played in. And slide guitar technique came from the Hawaiian music when bluesmen heard it on the radio in the ‘20s and ‘30s. And so forth and so on.

“It’s a wonderful gumbo that’s been brought together through the African-American experience. They made magic music, something that’s the root of all music popular in the Western world today. It’s stunning, wonderful and underappreciated. Stevie Ray Vaughan, Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix didn’t invent the blues.

“If I have a final thing to say, if you’re going to sing ‘Crossroads’ and you’re gonna add the verse from ‘Travelin’ Riverside Blues’ that Clapton threw in there – about ‘goin’ to Rosedale, take my rider by my side’ — I want white people to understand that we’re not ‘gonna buy a house by the river side,’ we’re gonna barrelhouse because Robert Johnson never thought once in his life about buying a house.

“Understanding that experience and the culture that gave birth to the music is critical to really understand the blues.”